Dr Henna Koivusalo is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Bristol, UK. She won the 2025 London Mathematical Society Anne Bennett prize for her work in cut-and-project sets and fractal geometry, and her contributions in mathematics outreach.

1. What’s your earliest memory of doing mathematics?

When I was little, I loved things like my pets, writing poems and knitting. As far as I can remember, I had absolutely no particular interest in numbers or puzzles. I only picked (the Finnish equivalent of) Further Maths because I wanted to become a vet, and I expected to really struggle with it!

But I’d always been generally anxious about right and wrong, and what’s really real and things like that – I read a lot of philosophy books at some stage. And then when I learned about proofs in Further Maths, I felt comforted by the certainty of mathematics. It was an answer to this question that I hadn’t known how to ask. In the end I didn’t even apply for the vet school.

Though I still expected to struggle with maths, it was the only thing I wanted to study at university.

2. How has mathematics education changed in the time you have been involved in it?

I received my education in Finland, and since then have taught in three different countries, so it’s hard to disentangle different local cultures from times changing. But comparing my own students’ experience to mine, I am sorry that I can’t give them as much individual attention as we received as students; my classes were much smaller. On the other hand, the structure of the maths degree is totally different – we spent a full year on just Analysis and Linear Algebra, and students these days get started straight away with many more topics, and coding on top for good measure! Theirs is a much more versatile degree.

3. Tell me about a time in your career when something totally flabbergasted you.

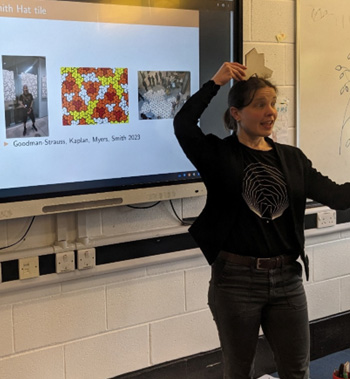

It’s going to have to be the discovery of the Hat tile in 2023. This is a single tile shape that, when fitted together correctly, can cover a whole infinite plane without gaps or overlaps, but the pattern is aperiodic, that is, never repeats exactly. I’d looked at the problem myself at some point, and had a relatively strong intuition that if such a shape existed, it would somehow have to carry an ‘infinite amount of information’ to stop it from creating a repeating pattern, and so I imagined it would have to have a fractal boundary. But it turned out to be a simple 13-sided polygon made of pieces of hexagons! And it was discovered by an amateur maths sleuth, David Smith, which makes the story even cooler.

4. Do you practise mathematics differently in company?

Absolutely! Talking through a problem together at the blackboard with a collaborator is exciting, fast paced and fun! And then inevitably it reaches a stage – once you’ve hit the hard core of the problem – where you’re both just sort of staring at the board, or your hands. Then it’s better to go away and sit on your own by a window with some Simon & Garfunkel or something else pensive on the headphones, and sift through ideas and nail down details. It’s like breathing in and breathing out. There has to be a rhythm.

5. Do you think a brilliant maths teacher is born or made?

Over and over again I’ve thought: Now! Now I’m finally beginning to understand how to teach, and how to communicate maths. The content is not the hard part, though of course everything has to be well arranged and coherent. But the really tricky part is coming up with all the examples and analogues and specific words that help people engage, understand and remember. And then the impossible part is staying present with the people in the room and in dialogue with them. Maybe it’s easier for some people to pick the skills up, but I don’t see how anybody could be born with that ability.

6. What’s the most fun a mathematician can have?

I love it when there’s a totally new idea or a totally new connection, especially when it is only just taking shape. It’s like an exhilarating vertigo. A lot of research isn’t actually like that, most new results are much more incremental, or else you think you’ve uncovered some amazing connection but it turns out to be a load of hogwash. I have a good idea maybe once every 3 years or so. But when it happens it’s amazing.

7. Do you have a favourite maths joke?

I like this one:

A mathematician, a physicist and an engineer were each given a length of rope and asked to make an enclosure as large as possible for a bunch of sheep. The engineer solved the problem quickly: He put up an enclosure in a sort of square shape and said, ‘I’m not sure if that’s the best possible way to do it, but it’s big enough for those sheep.’ The physicist soon figured out that the optimal solution was to pull the rope into a circle. (The physicist is totally right here, by the way, due to the isoperimetric inequality.) But it was then the mathematician’s turn. He wrapped the rope around his middle (we have to imagine here a mathematician with a big belly so that his middle is his thickest part), and said, ‘I define myself to be on the outside.’

It's a pretty good summary of what maths is for me (and a little bit of friendly competition between fields is a good thing!).

Join the conversation: You can tweet us @CambridgeMaths or comment below.